Adam lost his cow; Adam found the night

Paolo Colombo

The central theme of the work of Avish Khebrehzadeh is the process of transformation of an individual and the resulting complex search for identity. The subjects of her drawings, still and animated, are hard to define: boys (or girls?) whose age and gender are unclear; animals of unrecognizable species; adults whose occupations are part of a fairy tale memory (animal tamers and sword swallowers) presented in bare scenes, such as fountain, a little circus ring, a few trees or an expanse of water.

Often the characters appear accompanied by a similar character, reflected in a pool.

On other occasions they change into different persons or animals, and come in and go out of the stories with grace and a slight air of sadness. These stories seem to be based on fairy tales but they are for adults, and they speak of miracles but also of the protection of the loved ones, of hopes dashed by the neglect of men and of things, of loneliness and sorrow.

The stories are simple and tell of simple things: the joy of a circus, the excitement of struggle, rest, as in Swimmers, Circus, Wrestlers and Siesta (video animation 1999). Coaxing, hypnotic music accompanies the images, which sets the rhythm and the emotional temperature of the action.

Avish Khebrehzadeh has lived in Iran, in Italy and in the United States – in three continents. The feeling of disorientation and the problems of adjustment are part of her cultural and political baggage. To all this Avish Khebrehzadeh adds her sensitivity to the periods of generational transition, and in particular, to those going from infancy to childhood and from adolescence to adulthood.

In Itinerant (video animation, 2002) a man finds a strange creature lost on the seashore. The man brings it with him to a house in the village where he lives. Once there, the strange child or animal does not act like “the others” and does not succeed in adjusting to the new domestic environment. It is not understood and it suffers from that. The man wonders who its parents are, and whether it might not be better to bring it back to where it was found. Then a man and a woman come to take it back. They have a cup of tea and disappear. The child returns to the se; that is, to its own obscure nature. This is the story.

Itinerant is a short tale that defies the usual contours of its kind. It tells about a child (the hero) who was lost and who was picked up by a stranger. Brought to ne surroundings unhearing and unresponsive to its nature, it was rejected. The true parents find it and recognize it. This time of recognition (the traditional revelation of fairy tales) does not bring it happiness, but instead increases the creature’s sensation of its otherness and its inability to find an identity, a place where it belongs.

This story is a model of the artistic practice and content which Avish Khebrehzadeh brings to her work. While it is true that the structure is that of a fairy tale, the subject matter is adult and modern. It is pervaded by the kind of knowledge to which Carlo Emilio Gadda gave the name “awareness of sorrow”.

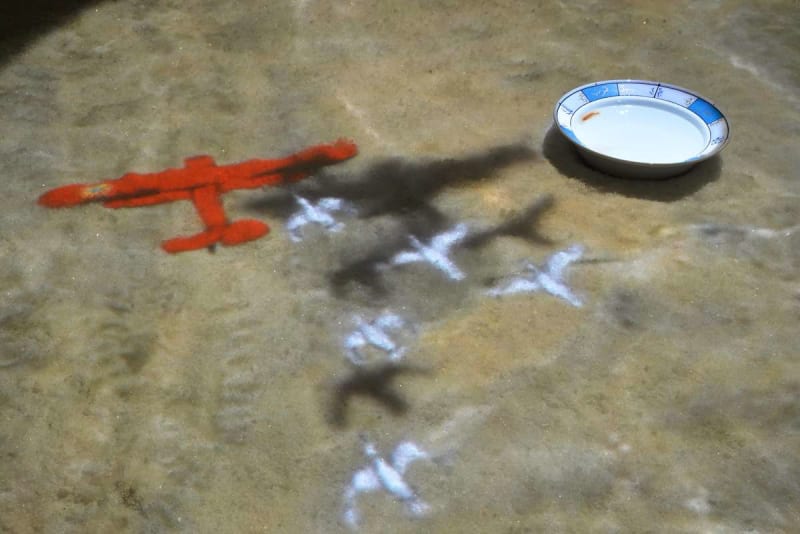

Distant Memory II (2003) and The Cow (2003) also belong in this context. Distant Memory II is a projection of a circus scene (a contortionist, a caged lion, a walking elephant and more) in a drawing four meters wide showing an audience under a circus tent. The Cow is the allegory of hope. It tells the story of Adam who has lost his cow. In the eyes of a little girl, Adam, The man who has lost his cow, “looks like a shepherd who has lost his sheep or a lover who has lost the woman he loves.”

As Adam looks toward the horizon, one can see the following words written on the screen:

The cow vanished

Like a voice in the alley

Like an aroma in the air

Like a shadow on the wall.

The final scene shows Adam drinking from a pond with a herd of cows.

Khebrehzadeh’s animation themes are repeated on still drawings on paper. She uses drawing techniques, with pencils and pastels mixed with traces of olive oil and watercolor on large sheets of rice paper. The penciled line is slight, and its uncertainty (which is deceiving) contributes to giving the scene its emotional dimension. Her materials are few and poor and the colors are austere, just like the colors we associate in our memory with mountains and remote villages.

In recent years her work has developed in accordance with guidelines defining the content in a similar way, although different in form. For years paper has been her preferred material, but it has now been replaced by gesso and wood. The dimensions of the paintings have been reduced to a format that would fit an easel or to the size of small travel pictures. The paintings made on wood show certain hardness, due to the hardness of the material, so that the lines, the shadows and the light of the images assume an etching-like quality, which suits the painted action perfectly. This is the case of Push-Ups (2006), belonging to the series The Blue Paintings, which may represent the acrobats we already seen in her work. Yet, today they no longer look like absent-minded teenagers, but like determined men, in the full force of their manhood. A part of The Blue Paintings–blue indigo paintings, as the name suggests—is the Two Headed Calf by the Stairs (2006), a painting made on wood previously prepared with chalk. Just like all the other painting in the series, it is a night scene, an image that one can only vaguely feel, as in the best tradition of paintings of this kind. It reminds one of Whistler. The white color that defines the image slightly touches the main lines on the surface: the calf’s heads, the handrail, the chandelier, the steps of the stair.

I like to think that Adam, the character in one of her 2003 videos, still is a character in Khebrehzadeh’s work. Even more, he is her “Everyman”. No longer a boy, he looks at the world from the same emotional point of view, aware of the dark side of what he sees and takes in, of his dazzling visions (The Hippo, 2006) and of the mystery hidden in the night.